By Robbie Mallett

Dr Robbie Mallett is a sea ice scientist, currently over-wintering at Rothera Research Station in Antarctica as part of an eight-month research campaign for the DEFIANT project. Robbie explains the sea ice science he’s been working on through Antarctic winter, and the unexpected context of Antarctic historic sea ice lows.

Antarctica’s floating sea ice is now covering an unprecedentedly small area for the date, leading to widespread concern in the climate science community. In fact, sea ice conditions have been unusually low since 2017, suggesting that some sort of profound change to the system might have occurred around then. However, our scientific understanding of how Antarctic sea ice behaves remains poor, and we’ve so far failed to identify clear underlying drivers of the poor conditions that have prevailed since 2017. The BAS-led DEFIANT project aims to address this knowledge gap, and deliver a step-change in our understanding of sea ice behaviour in Antarctica.

Antarctic sea ice is a key component of what scientists call the Earth System. That term is based on the idea that Earth’s ecosystems, oceans, atmosphere and cryosphere are all related and interdependent. That’s certainly the case when viewed from the sea ice perspective. Antarctica’s floating ice cover plays a role in sustaining birds, marine mammals and the millions of tonnes of photosynthesising algae that support the Southern Ocean’s food web. The snow that’s held up by the sea ice is also able to reflect sunlight back into space, keeping the Earth cooler than it would otherwise be. Finally, when the sea ice forms each year it drives the Earth’s deep ocean circulation and sequesters huge quantities of carbon dioxide (absorbed from the atmosphere) near the ocean floor. We would therefore like to monitor the health of Antarctica’s sea ice with earth-orbiting satellites as effectively and in as many ways as possible.

My research group (the University of Manitoba’s Centre for Earth Observation Science) is collaborating with DEFIANT to better understand sea ice through the lens of its thickness, as estimated by satellite technology. My colleague Vishnu Nandan and I are spending the winter at Rothera Research Station in West Antarctica, where we’ve been monitoring the sea ice with a radar instrument that’s designed to mimic the operation of satellites. We’re also equipped with a raft of other instruments such as laser-scanners and infrared cameras to fully characterise the winter behaviour of the sea ice around Rothera. Vishnu and I are particularly interested in the snow that sits atop the sea ice, and how it interacts with radar waves and laser pulses that are emitted from satellites.

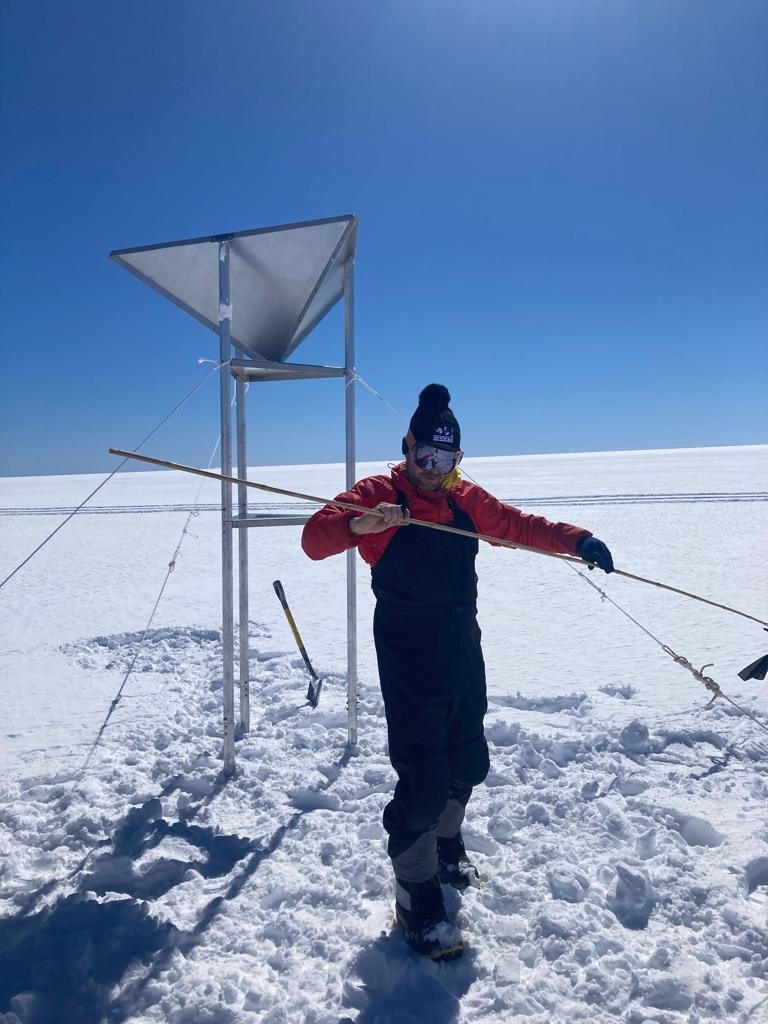

Vishnu and I working with our station leader to set up instruments on 30 cm thick sea ice. The white sea ice that we’re standing on has been around long enough to accumulate snow, but the grey ice in the background is less than ten centimetres thick, and can easily be destroyed by strong winds. Photo: Vicki Warke, British Antarctic Survey.

Unfortunately nobody told Antarctica that this was the winter of our big sea ice campaign! Because of the weak sea ice cover, we haven’t had many days out on the sea ice as it’s been very thin, the air has been dangerously warm, and the winds have been frighteningly fast. When these conditions combine, the sea ice can break away from the land and sweep our instruments, or even us, out to sea. In light of this hazard, we’ve become connoisseurs of the various weather forecasts available to us!

In response to the difficult sea ice conditions, Vishnu and I have been carrying out laser and radar investigation on a nearby glacier. This work will hopefully help us understand the basic physics behind the interaction of electromagnetic waves and snow, but also support the development of better satellite algorithms to retrieve the thickness of Antarctica’s ice sheets and ice shelves from space. We’ve also been carrying out a series of experiments on snow in Rothera’s Bonner Lab to better understand how brine migrates through snow on sea ice and can confound satellite algorithms.

Generating a very-high-resolution model of snow roughness using our laser scanner. This model can be compared to radar measurements to better understand how snow reflects radar waves. Photo: Vishnu Nandan, University of Manitoba.

It’s been a historic season for Antarctic sea ice, and it’s a season that’s not yet over. So watching the satellite numbers plunge while actually working here on the ground has been quite an experience. This year’s conditions are beyond what anybody predicted, so it’s both intimidating and a privilege to be tasked with investigating them. While we can’t be certain of much right now, we can be confident that many exciting discoveries await.